The man who gave his life for a friend

The Story of the Tragic Deaths of John Gannon & John Gregg

"Greater nobility of mind and heart could no man show than did John Gregg, who, regardless of the risk he was running, bravely descended the shaft in which his colleague was lying in a helpless condition, with the heroic object of recovering him, and himself fell a victim to the presence of gas." Salford City Coroner, Mr A. Flint, 25 October 1927

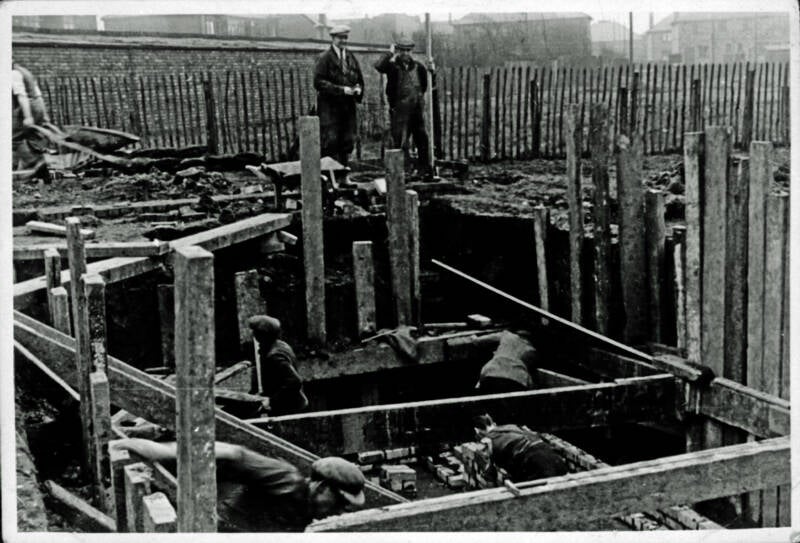

In the early days of constructing the Ambassador Super Cinema in Salford, a heartbreaking accident claimed the lives of two dedicated workers, John Gannon and John Gregg. This page honours their memory and details the events of October 1927, drawing from historical records and eyewitness accounts. As part of the "People" section, it highlights the human stories behind the cinema's creation, reminding us of the risks faced by labourers in that era's construction projects.

The Incident

Work began on preparing the site for the Ambassador's foundations when tragedy struck on the morning of Saturday, 22nd October 1927. Two workers, John Gannon (31) of 36 Jennings Street, Salford, and John Gregg (31) of 10 Chapel Street, Pendleton, tragically lost their lives. John Gannon was a steadfast labourer, known among his mates for his quiet reliability. John Gregg, similarly devoted to his craft, had married Mary Somers in April 1923 at Barton Upon Irwell, Lancashire—a quiet union that spoke to the simple joys of life in the industrial heartlands. The couple had no children, leaving Mary to face unimaginable grief in the years ahead.

The site had previously been an old cinder tip, and although this was known to Gerrard and Sons Ltd., of Swinton, who had been contracted to prepare the site for building, there was a lack of awareness about the dangers posed to their workers when digging the shafts.

The men were sinking a shaft as a preliminary to laying the foundations for the new cinema. It is believed that gases had collected at the bottom of the 25ft shaft during the excavation over the previous fortnight.

On that fateful Saturday morning, the two men, along with another workman, Edward Wadsworth of Long Street, Swinton, stripped the planks covering the mouth of the shaft, and John Gannon descended into the pit. Upon reaching the bottom, he was seen to collapse, and Wadsworth lowered John Gregg in an attempt to rescue him. As Gregg descended, he too became affected by the fumes when he reached about 15 feet down. Retaining his grip on the rope, he succeeded in reaching Gannon and clasped him with his arms before losing consciousness himself. Wadsworth, meanwhile, attracted the attention of nearby residents and contacted the Police and Fire Brigade.

A Hidden Hazard Beneath the Cinders

The shaft was being sunk through an old layer of cinders and ashes, the long-forgotten waste of earlier industrial fires on the site. In such material, oxygen can slowly be consumed and replaced by heavier gases like carbon dioxide, creating an invisible pocket of “blackdamp.” In a deep, unventilated shaft this gas can settle overnight without any smell or warning. Anyone entering such an atmosphere can collapse within seconds. It was this silent buildup that the coroner identified as the “poisonous gases” responsible for the deaths of Gannon and Gregg.

The Rescue Efforts

An eyewitness described the rescue to a reporter at the time:

“Men came running from all directions and peered into the mouth of the shaft. A man tied a running noose in the windlass rope and let it down into the pit. He drew it gently over the head and shoulders of Gregg, who was on top of Gannon. We all pulled at the rope. We were surprised to find that both men came to the surface. That was because Gregg’s arms were tightly wound around Gannon’s body. Gregg’s last thought, presumably, had been to clasp Gannon and raise him. We had the greatest difficulty in unclasping Gregg’s arms.”

Another witness, Joe Barrick of Earl Street, Swinton, added: “I saw the rope from the winch dangling within a foot or two of the men in the shaft. The man underneath lay flat on his face and was absolutely still, and Gregg lay on top of him, grasping his clothing. He was badly gassed, and as I looked, he relaxed and lay still."

Despite attempts at resuscitation by Wadsworth and PC Harry Spencer, both men sadly died at the scene. At the Coroner’s inquest, Edward Wadsworth said that without hesitation, Gregg had gone immediately to Gannon's assistance but collapsed when some feet from the bottom. "I ran to inform the Police," he said, "and after the assistance of pedestrians had been enlisted, the men were hauled to the surface. It was a great shock to me, and I cannot speak too highly of Gregg’s courage and self-sacrifice."

Recent information from the Carnegie Hero Fund Trust clarifies that John Gannon's legs became entangled in the rope during his collapse, rather than being deliberately attached or tied to it. This detail explains why pulling him up directly was not attempted and underscores the necessity of Gregg's brave descent into the shaft. In a final, desperate act of brotherhood, Gregg clasped Gannon tightly in his arms before succumbing himself—his grip so unyielding that rescuers later struggled to pry them apart.

This instinctive bravery may have been forged in the fires of shared hardship: though records are sparse, it is possible that the two men, both Salford locals in their early thirties, had served together in the same regiment during the Great War, just a decade earlier. Such bonds, tested on the battlefields of Europe, could explain why Gregg plunged into danger without hesitation, prioritising his comrade's life over his own.

The Inquest and Praise

The coroner praised Gregg's selfless heroism, stating, "Greater nobility of mind and heart could no man show than did John Gregg, who, regardless of the risk he was running, bravely descended the shaft in which his colleague was lying in a helpless condition, with the heroic object of recovering him, and himself fell a victim to the presence of gas. These men lost their lives by being asphyxiated in a shaft, twenty-five feet deep. They lost their lives in a manner that cannot fail to call forth the deepest expressions of sympathy and regret, and also, in regard to one of the victims, great admiration. "

The coroner added, " There may be a matter to consider whether the employer took reasonable precautions for the safety of the men."

Mary Gregg, John Gregg's widow, provided crucial insight during the inquest. She revealed that her husband had felt drowsy the night before the incident, suspecting it was due to the foul air in the shaft. She said, "He thought the drowsiness was due to the bad air in the shaft."

Wadsworth, who went to report the accident to the police, said they did not try to pull Gannon up despite the rope entanglement. The Coroner suggested, “You might have brought him up.” to which Wadsworth replied, “It was just the thought of the moment.“

Police Constable Harry Spencer, who had applied artificial respiration, was commended by the Coroner for the admirable promptitude which he had shown.

Wadsworth, said Mr Richardson, the manager, had been to inspect the workings the day before. Mr. Richardson, a director of Gerrard and Sons, stated that there had never been any complaint about foul air or smell. He recalled that an employee had once told him that they had to "bat the air," but Richardson believed this simply meant it was warm.

The Coroner pressed further, stating, “I suppose you now realise the danger which exists in excavating in a confined place?” to which Mr Richardson replied, “I do realise this danger, but I have never come across it previously.” He knew the site was an old cinder tip. The Coroner asked, “Do you know foul gases do accumulate in these pits? " Mr. Richardson replied, “I believe so, but I have never known anybody to be overcome.” The Coroner continued, “There are no appliances for use in the case of foul air?” Mr Richardson stated, “We had none on the job. " The coroner then asked, ” Are any tests ever made?” to which Mr Richardson replied, “Not in this case.” The coroner queried, ” Have you known any tests in other cases?” to which Mr Richardson said he did not.

It was confirmed that the cause of death was asphyxia from inhalation of poisonous gases. Answering the Coroner, a doctor said the gas might accumulate overnight. He understood that they had excavated through cinders and got down to the sand, which the gas would not permeate as it would through cinders. The Coroner noted that this was the first case of its kind in the district, and he was sure Messrs Gerrard and Sons would be only too anxious to take the necessary precautions in future. The evidence did not reveal any negligence, and the verdict would be "Death from misadventure"

Aftermath and Legacy

The directors of the Ambassador Super Cinema decided, although no responsibility attached to their company, “to mark their great regret at the unfortunate accident” by donating the first day’s proceeds to the dependents of the two men when the cinema opened.

There is no record that the men’s employer, Gerrard and Sons, compensated or assisted the men’s dependents in any way, which is not to say they didn’t; we don’t know.

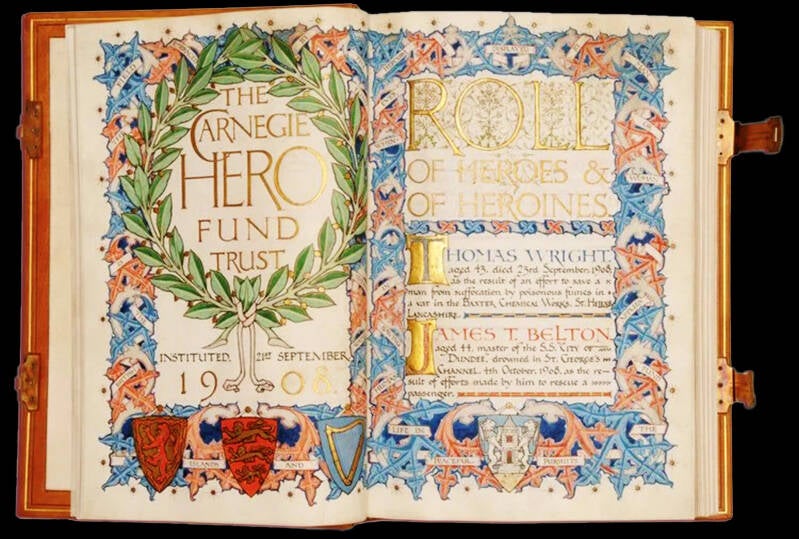

A copy of John Gregg's entry in the Roll of Honour.

Kindly provided by The Carnegie Hero Fund Trust

John Gregg’s widow, Mary Gregg, received a heroism award certificate from the Carnegie Hero Fund Trust on behalf of her deceased husband.

Recent correspondence with the Trust reveals that John and Mary had no children. Gregg’s widow was supported by the Trust for the rest of her life; she died in 1961, at the age of 66.

This record of support also indicates she never remarried.

Both men’s dependents went on to receive half each of the proceeds from the Ambassador's Christmas Eve opening night, amounting to £112 and 1 shilling.

While no further details on John Gannon's family are currently available, the Gregg family's story adds a layer of personal legacy to this poignant event.

This tragedy underscores the importance of worker safety in historical construction, lessons that have shaped modern practices.

References

- Carnegie Hero Fund Trust. (n.d.). Heroism award certificate to John Gregg’s widow. Carnegie Hero Fund Records.

- Gerrard and Sons Ltd. (1927). Site preparation and safety reports related to the Ambassador Cinema construction [Company records].

- Manchester Evening News. (1927, October 22). Two men overcome by fumes in shaft at new cinema site, Salford.

- Manchester Evening News. (1927, October 25). Inquest on deaths of John Gannon and John Gregg: Coroner praises heroism.

- Newcastle Journal. (1928, January 27). Ambassador Cinema opening night proceeds divided between dependents of tragedy victims.

- Salford City Coroner's Office. (1927). Inquest transcripts and witness statements for John Gannon and John Gregg [Archival records].

- Salford City Reporter. (1927, October 26). Tragic shaft accident at Pendleton cinema site: Eyewitness accounts from rescue.

Create Your Own Website With Webador